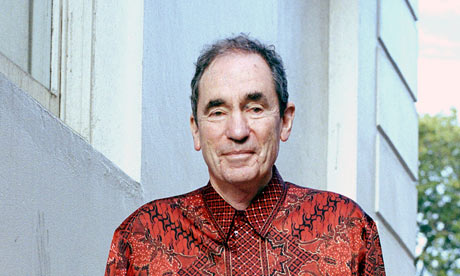

Albie Sachs, arguably the world’s most famous judge, was fleetingly in the UK last week, primarily to tell the story behind the judgment he made in South Africa not to send a woman to prison because it would infringe the human rights of her three children.

Even by the standards of a judge responsible for some of the most progressive legal judgments, such as ruling that it is unconstitutional to limit marriage to a man and a woman, the case of S versus M, now being cited in courts worldwide, is remarkable.

“Judges are the storytellers of the 21st century,” says 74-year-old Sachs, who told an international audience of human rights experts in Edinburgh that the first mindset that needed to be changed in the now historic case was his own.

At first sight, he had intended to throw out an appeal on behalf of Mrs M, who was facing four years in jail for up to 40 counts of credit card fraud that she had committed while under a suspended sentence for similar offences. “I remember drafting an extremely dismissive response. I said: ‘This doesn’t raise a constitutional question. She simply wants to avoid going to jail. She doesn’t make out a case, and her prospects of success are zero.’ “

It was a female colleague, another of the 11 green-robed judges in South Africa’s constitutional court, who insisted that the case be heard. She argued that the human rights of the accused woman’s children were not being looked at separately.

“She said: ‘There is something you are missing. What about the children? Mrs M has three teenage children. She lives in an area that we politely call fragile, an area of gangs, drug-peddling and a fair amount of violence. The indications are that she is a good mother, and the magistrate gave no attention to the children’s interests.’

“The minute my colleague spoke to me about the importance of the three teenage children of Mrs M, I started to see them not as three small citizens who had the right to grow up into big citizens but as three threatened, worrying, precarious, conflicted young boys who had a claim on the court, a claim on our society as individuals, as children, and a claim not to be treated solely as extensions of the rights of the mother, but in their own terms.”

As a result, Sachs created a legal precedent in 2007: a woman who otherwise would have gone to jail did not have to, because of her children’s rights. “We could have said the children’s rights must be considered but sent Mrs M to jail anyway, perhaps for a lesser term. But that would not have changed anything.”

Court responsibility

Although three judges dissented from the majority verdict, the precedent was set in South Africa that – at least in borderline cases – primary caregivers of children should not be sent to jail. And if the court decided to jail a primary caregiver, it had to take some responsibility for what happens to the children. “The court can’t simply say that she should have thought of that before she committed the offence, or that she can’t hide behind her children.”

A QC in the audience at Sachs’s lecture on the case – his first outside South Africa – said he had cited S v M in the court of session in Edinburgh, in a case of two children who live in London with their grandmother and who were facing deportation after nine years because their mother, a Jamaican citizen, had been arrested for drug dealing in Aberdeen.

At the time he was drafting the judgment, Sachs did not know of any country that took the rights of offenders’ children into account, but he subsequently discovered that similar ideas were being framed in Scotland in a report by the then children’s commissioner, Kathleen Marshall.

The report, Not Seen, Not Heard, Not Guilty, argues that the rights of offenders’ children to family life under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child are systematically ignored by the court system. The report found that almost two-thirds of prisoners in the Cornton Vale women’s prison in Stirling had children under 18, but there was no provision to take their rights into account during sentencing.

“This was astonishing,” Sachs told the audience. “In a totally different legal system, in a totally different society, a conclusion was being reached that is almost identical. It showed that the time has come for new ways of thinking.”

Sachs says that South African courts are also taking a new approach to dealing with young offenders. “We use as much diversion as possible from the criminal justice system. We try to use the family and the community. We try to find ways of helping them to live together in the same neighbourhood, and we use apology and reparation and reconnection, rather than institutionalising and isolating the offender from the community and placing the offender with other offenders in a youth culture of marginalisation and anger. Offenders are encouraged to see themselves as part of the community.”

For Sachs, courts like his are key to liberal democracy. “I see the role of judges in the world of diversity and conflict as striving for the protection of human dignity. The court is very, very important in terms of the basic norms, standards and values of the society, which continually evolve and develop.”

Sachs – an ANC veteran who was exiled to the UK in the 1960s and later moved to Mozambique, where he lost an arm and an eye to a car bomb planted by South African agents in 1988 – is frustrated by the negative perceptions of what has been achieved in post-apartheid South Africa. He hopes that football’s 2010 World Cup, whose logo he helped to choose, will provide an opportunity for visitors to see a country that has “tremendous energy and enthusiasm”. He says: “We still have huge problems associated with poverty, unemployment and inequality, related to the racist past, and we have pressure from the millions of refugees from problems in other African countries. But our democracy is well entrenched. We have regular elections. They are manifestly free and fair.

Peaceful solutions

“We have a lively press and a strong civil society. Something like 10 million people have moved from shacks into brick houses at no cost to themselves. Electricity is becoming more accessible. We are confronting our problems and trying to find peaceful solutions.”

Sachs, who has sat in the constitutional court since his 1994 appointment by Nelson Mandela, will soon bang the gavel for the last time. He says he does not use “the R-word” – retirement – but court ends for him at midnight on 11 October. After that, he wants to concentrate on giving “as much daddy as he can” to his two-year-old son Oliver (named after former ANC leader Oliver Tambo) by his second wife, architect Vanessa September, 30 years his junior. He also hopes to make a feature film, but won’t be drawn on any details.

Meanwhile, he has just released The Strange Alchemy of Life and Law, the latest in a series of autobiographical books. In a chapter called The Judge Who Cried, Sachs reveals that he found himself in tears after ruling that South African Airways could not discriminate against an air steward with HIV. “It had not just been because of the impact of HIV on our country,” he wrote. “The tears had come because of an overwhelming sense of pride at being a member of a court that protected fundamental rights and secured dignity for all.”

Curriculum vitae

Age 74.

Status Married to second wife, Vanessa September; one son. Two sons from first marriage.

Lives Johannesburg and Cape Town.

Education South African College Schools, Cape Town; University of Cape Town, degree in legal studies; Sussex University, PhD.

Career 1994-present: judge in the South African Constitutional Court; 1977-94: law teacher in exile in Mozambique; 1966-77: law teacher in exile in the UK; 1956-66: barrister in Cape Town.

Books The Strange Alchemy of Life and Law (OUP, June 2009); The Free Diary of Albie Sachs (2004); Soft Vengeance of a Freedom Fighter (1991); Justice in South Africa (1974); Sexism and the Law (1979); The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs (1966), and others

Interests Films, writing, sport.