Usually I manage, for a couple of days at least, to be one of the arts marathoners who dash from show to show at the Edinburgh Festival and Fringe. I like to pick a theme – it makes it easier to sift through all that is on offer. This year, it was – history within living memory, the people who shaped our era.

Here are some of the things I saw:

The Edinburgh Book Festival

1 In the sights: Nicola Sturgeon Frankly

Veteran journalist Kirsty Wark was very much in the driving seat at this event – it was less a fireside chat and more an extended episode of Newsnight. We did hear in passing that, despite her cool demeanour, Sturgeon suffered from anxiety and panic attacks during her time in office, doubled up on the floor with stomach cramps at times. I suspect she is not alone in that – though it is not something ex-leaders often confess to.

In the last few minutes, Wark asked about independence. Sturgeon said: “Sometimes things feel stuck and impossible, and then they start to move much more quickly than you think”.

She gave the example of 1992, her first year as an electoral candidate. That general election was a surprise win for the Conservatives under John Major. Those who had been campaigning for decades for a Scottish Parliament were certain it was off the table for another generation. And yet, a few years later, it was in session and she was one of the first members.

Sturgeon’s legacy is that independence for Scotland is no longer unthinkable. I suspect that is why she attracts such vitriolic criticism from Unionists. Most younger Scots support it and sociologists do not think this is a life cycle phenomenon. Two-thirds of Scots think Scotland will be independent in the foreseeable future. Nine out of ten in Northern Ireland agree Ireland will be united in the same time scale. Perhaps the time has come to start discussing calmly what a constructive and cooperative post-UK future might look like for this archipelago

2 Liu Zhenyun: Behind the Mask of Humour

Liu Zhenyun writes, in an absurd and ironic way, about the rural world so many Chinese have left behind. Humour, of course, can be dangerous – in one of Liu’s stories a man chokes on a fishbone after being told a joke, leading to a sign in the restaurant: “No Public Joking”.

My impression that Liu is a literary lion was increased by the rapt, capacity crowd and the fact that the automatic surtitles for the English part of the event rendered his name as “Leo Genuine”.

Liu raised a lot of laughs from the Mandarin speakers in the audience. But the translator had some heavy lifting to do. When Liu said his publisher wanted him to write a book called Ground Covered in Duck Feathers, she had to add as a hasty aside that the bestseller known in English as Tofu, is Ground Covered in Chicken Feathers in the original. That took a couple of minutes to land.

Liu said some things that stuck with me. He was asked why he always writes about the country people, the pig butcherers and tofu sellers. He answered that there are no little people in fiction.

In real life, when Donald Trump speaks, the whole world hears him. When the people in his village speak, nobody hears them. But every character in a novel is heard just the same as any other.

An audience member asked if Liu thought that people are shaped by the epoch they live in or if they shape history. He answered that the little people don’t have a chance of shaping history – alone. But acting together, they are the most powerful force there is.

And he seemed to say, I may have got this wrong, that sometimes the silence of the people is an act of resistance – “the silence is deafening”.

3 Sam Dalrymple: The Legacy of Partition

Sam Dalrymple’s book Shattered Lands is about the five partitions that broke up the once vast territory of British India. Dalrymple asked why the central, catastrophic 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan – the largest forced migration in human history, with 12 million people displaced and one to three million dead – isn’t more widely recognised as one of the defining moments of the 20th century.

Some epoch-shaping characters emerged from his telling. Ruttie Jinnah, the neglected, drug-addicted, much younger wife of the founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Jinnah, killed herself, an event which was said by many to have changed her husband’s character overnight.

When Lord Mountbatten arrived to oversee the departure of the Brits, he accelerated the timeline for independence from 18 months to just 77 days – a decision that many believe contributed to the chaos and bloodshed. Why did Mountbatten do this? Dalrymple had two alternative theories – one, he wanted to get back to London for Princess Elizabeth’s wedding, which he helped organise. Two, he was in fear of his life and wanted to get the Brits out before the place exploded.

The event was chaired by Anita Anand with empathy and insight. She spoke movingly about her own family’s experience of Partition, describing how they had lived peacefully for centuries in a Punjabi village alongside neighbours of different faiths – until the border was abruptly drawn with no planning, causing panic. Some families, including hers, helped people from the other side to escape, but the violence was overwhelming and has led to much of the bitter division that still remains: “When you’ve had a family member slaughtered, you don’t forgive.”

The Edinburgh International Festival

1 Shostakovich’s 10th symphony, the LSO, Usher Hall

We had an explanation of the music from conductor Antonio Pappano. Shostakovich’s last symphony was performed in 1953, a few months after Stalin died. About three-quarters of a million people were judicially executed on political charges during Stalin’s reign of terror.

There was a six-year gap between the ninth and tenth symphonies during which Shostakovich must have kept his musical notebooks well hidden. I remember reading in the programme notes for an EIF concert long ago about how he would write music sitting on the stair of his tenement, in the hope that if the secret police came for him, they would leave his family alone.

The second movement, the scherzo, which means joke, was described by Pappano as “the face of Stalin”. It is full of frenetic energy, punctuated by the rat-a-tat of what sounds like a firing squad.

2 Make It Happen, NTS, Festival Theatre

This is an ambitious attempt to craft an evening’s entertainment from the global financial crash of 2008. Brian Cox was entertaining as the ghost of Adam Smith; Sandy Grierson played the central character of Royal Bank of Scotland supremo Fred Goodwin with brio. I enjoyed the show – and it allowed me to womansplain the crash to my young associates in the bar afterwards.

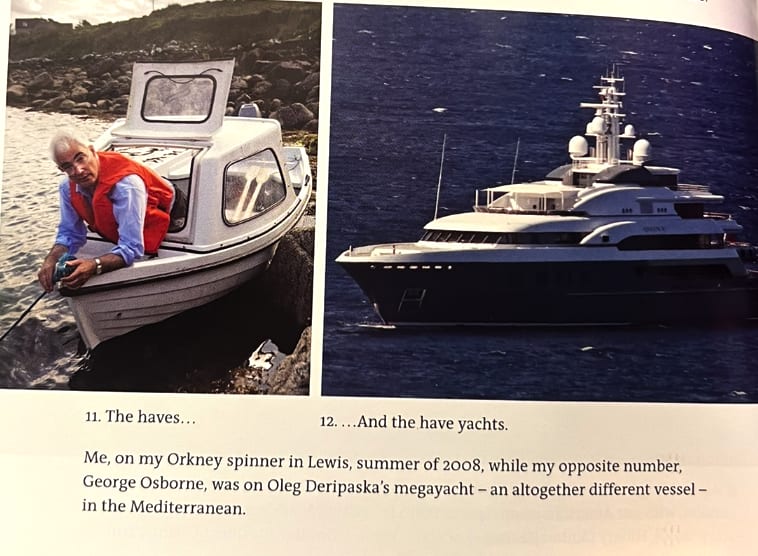

The play actually sent me back to Alistair Darling’s compelling book Back from the Brink, from which some of the play’s key scenes – such as Goodwin turning up announced at his Edinburgh home with a gift-wrapped panettone – are drawn.

Darling describes in the book how, when sailing his wee boat in the Hebrides, he would sense the wind and water changing before it was obvious. In August 2008, he gave an interview, while in the family home on Lewis, to Guardian journalist Decca Aikenhead, where he said the biggest downturn in post-war history was round the corner. There was a media storm and he was branded a dour Scottish doommonger. Two weeks later, Lehman Brothers collapsed.

My favourite scene from the book is not in the play. Darling writes that the UK under the prime ministership of Gordon Brown had taken the presidency of the G7 and was able to use it to create a coalition. It was the way the world’s major economies stood together that eventually calmed the markets. At a crucial juncture, there was a meeting in Washington. Darling was in the last car of a long entourage and ended up outside the gates. He had to talk his way past security and up to the White House where the doors had already been closed. When he was admitted, far from being annoyed, he was pleased to find that George W Bush remembered his name.

I felt a bit sorry for real-life Fred Goodwin, who still lives in Edinburgh. He was culpable of course, but in the play, he is made to carry the can for the whole mess. Like other banking chiefs across the world, Goodwin was the product of a system which at that time encouraged – and gave huge rewards for – risk-taking.

Darling describes him in his book as aloof. There may have been private queasiness and anxiety attacks. Surely bankers across the world were waking up in cold sweats as the liquidity – the system of the banks lending each other money overnight to hide their general insolvency – started to jam up?

One thing puzzled me. The play makes several references to Goodwin’s humble origins in Ferguslie Park, a suburb of Paisley. The fact that Goodwin grew up in a council house was not unusual in post-war Scotland. He attended Paisley Grammar School alongside eminent journalists Andrew Neil and Will Hutton. He was not exactly a diversity hire.

In fact, Darling describes his unease after meeting the board of RBS for the first time, a couple of years earlier. Apart from this one guy from Planet Glasgow, all the others were from Edinburgh. (I am guessing South Edinburgh).

At that time, RBS had become the biggest bank in the world. “Where was the American? Where was the expert on Asia?” Darling wondered as he left.

The Fringe

1 A Noble Clown, Scottish Storytelling Centre

It was disappointing that Make it Happen contained not a smidgeon of Scots. When the ghost of Adam Smith arrives, he conveys his Scottishness, as so often in the UK media, by swearing. It is as if the play is so desperate to be liked by London critics or to get a London transfer that any Scots word has to be self-censored out.

It was a treat after this to see Michael Daviot performing his tribute to Duncan Macrae. Macrae was a brilliant actor who devoted his life to Scots theatre, although other opportunities beckoned.

That generation of Scottish theatre people was given confidence by the success of The Three Estates, which was adapted by my grandfather, Robert Kemp for the 1947 Edinburgh Festival. Of course, many scoffed at the idea that a 16th-century morality play in Scots could find an audience – but that was proved otherwise. The play was a smash hit and played to packed houses. Macrae played the role of Flatterie, the only vice who escapes the gallows, and Daviot performs one of his speeches in the show. Macrae went on to fill theatres with many Scots plays: Gog and Magog, Jamie the Saxt, the World’s Wonder, Let Wives Tak Tent.

Scots is intimidating on the page, but on the stage it can come alive. Daviot is a master of Scots as a theatrical language – I have not heard anyone as good for decades.

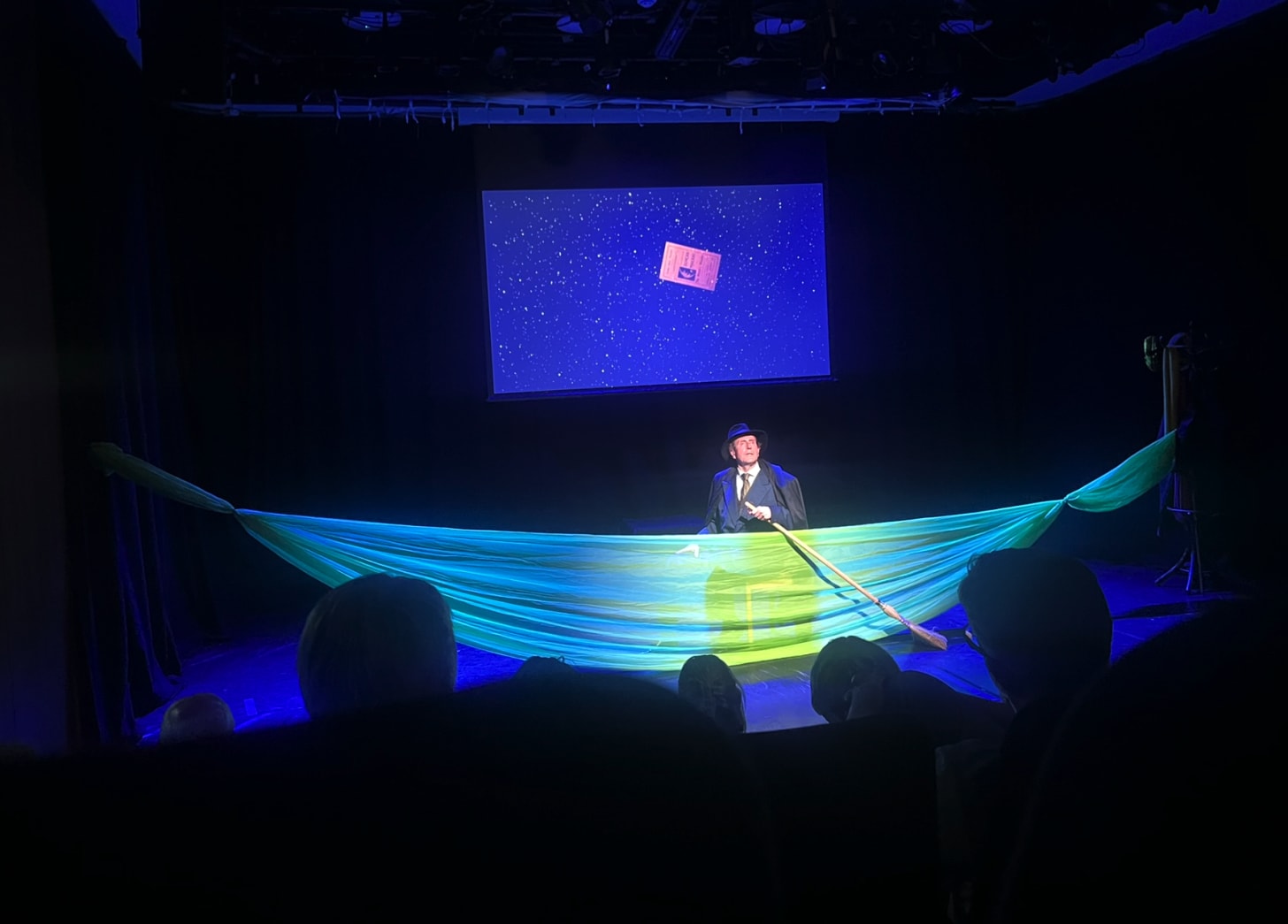

Daviot ends the play with a speech from the World’s Wonder by Alexander Reid which he delivers from a boat made with a sheet of fabric.

I’ve set a course ayont the last kent star.

Gin we win through, we’ll burst the bands o space

And beach the morn upon infinity!

Cherish a’ wonder. Teach the bairns tae dream –

There’s nae sic riches as imagination.

2 The Invisible Spirit, venue 45, Jeffrey Street

This is a dramatisation of a book about post-war Scotland by the late Kenneth Roy, a journalist and one-time colleague. The one-hour play is built around the character of Jimmy Reid, an important figure in Scottish history. This play again sent me to the text, a signed copy of which has been sitting in my study for years, pretty much undisturbed.

I970 was the first time that Scotland voted differently from England in a general election. A Conservative government was elected under Edward Heath. Scotland voted Labour. A year later, Westminster decided to abandon support for the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders.

Under the Labour government, the unions at UCS had participated in a painful transformation that involved the loss of 3,000 jobs. By late 1970, the order books of all four of its yards were full and productivity had improved considerably. But the company had been undercapitalised initially and it needed £6 million to rebalance its books. Instead, the Conservative government announced that “nobody’s interests would be served” by bailing out lame duck industries and pulled the plug, with the immediate loss of 7,000 jobs and a whole ecosystem that supported the yards.

Roy writes that the legendary Labour MP and former Secretary of State for Scotland “Willie Ross was reported to be trembling with fury. The former army major told his fellow MPs that one of the saddest moments of his life had been going through Clydebank in his Highland Lights uniform the day after its bombing by the Germans. ‘The blow delivered by the government is even worse than that’.”

Heath then went on a yachting holiday. Jimmy Reid and his fellow shop steward Jimmy Airlie led the famous work in where the men took over the yards and said they refused to leave and would continue to work for no pay.

Reid’s televised speech to the assembled men was watched around the world. He said: “There will be no hooliganism, no vandalism. Because the world is watching us and it will be up to us to conduct ourselves with responsibility and maturity.”

They had a lot of support – red roses were delivered from John Lennon and Yoko Ono. But the protest eventually failed and the yards were closed.

The play ends with Roy’s last vignette from the book. In 1975 when the Queen switched on the first North Sea oIl pipeline at Dyce.

“Far out in the North Sea 1,300 workers on the first of the Forres platforms looked forward to a celebration lunch. But at Grangemouth, there was little sign of ;one of the biggest public relations festivals of modern times’. A BBC reporter – who went on to write this book – stood outside the refinery on a late autumn day, trying to sound excited about the first tiny container of North Sea oil which had been thrust into his hands….The reporter was not asked to return the oil. He kept it in its container and it moved with him from house to house. After one such move, he noted that the contents had vanished. He wrote to that effect in a newspaper, thinking it a neat metaphor but was corrected by a scientific reader who assured him that, in his expert opinion, a residue remained. What was true of the contents of the bottle may also have been true of the life of post-war Scotland: that the spirit of the nation, though invisible to the naked eye, never quite evaporated.”