Our wild swimming anthology is available to pre-order and will be published on September 11. We hope to see some of you at our September book events

-

London: Hatchards, Picadilly, book signing September 18, 1.30 pm

-

London: Daunt Books, Hampstead, London, September 18, 6.30 – 8pm Tickets £6 including a drink, September 18 – 7 – 9.30 pm

-

Brighton: Kemptown Books, September 19, 7-9 pm, tickets £3

-

Helensburgh: Royal Scottish Geographical Society, Victoria Halls, September 25, 7.30 pm

“Natural water,” wrote Roger Deakin in Waterlog “has always held the magical power to cure.” Swimming in open water has definite health benefits of which we are now very conscious. Perhaps we lovers of cold immersion, though, sometimes overclaim for them.

Jane Austen also lived through a craze for sea bathing. There was one at the turn of the 19th century, which she satirised in the unfinished novel Sanditon, which she was working on at the time of her death.

“The sea air and sea bathing together were nearly infallible, one or the other of them being a match for every disorder of the stomach, the lungs or the blood. They were anti-spasmodic, anti-pulmonary, anti-septic, anti-billious and anti-rheumatic. Nobody could catch cold by the sea; nobody wanted appetite by the sea; nobody wanted spirits; nobody wanted strength. Sea air was healing, softening, relaxing fortifying and bracing seemingly just as was wanted sometimes one, sometimes the other. If the sea breeze failed, the sea-bath was the certain corrective; and where bathing disagreed, the sea air alone was evidently designed by nature for the cure.”

Robert Burns’ sceptical biographer Dr James Crichton-Browne, a collaborator of Charles Darwin. was less than impressed by the medical advice of that era that Burns should go sea bathing in the weeks before his death.

“So this broken-down man, who had seldom left his house for months and had spent most of his time in bed, who could scarcely stand upon his legs and bore on his countenance the pale cast of death, was sent to bathe in the open sea of the Solway, where bathing is, at its best, only possible for two weeks in the month [of July], owing to the state of the tides, and even then after much wading to obtain any depth of water. He was also to bestride and jolt about on a Rosinante.” [horse riding was also prescribed].

Clearly, open water swimming is not a cure-all for either mental or physical illness – but many find it helps in difficult moments, and there is a chapter of our book called “Well” in which we delve into these. Vicky writes in the intro of her own experience:

“It was bobbing around on Lough Mask in Ireland, staring up at an infinity of grey, that I found solace after the death of my brother. It felt as if he was somewhere out there in that sky, or in the water that held me so lightly. Not long after, when the menopause hit me sideways and off guard, the thrill of immersion in cold water, of being body-slammed by the waves, picked me up.”

Freya Bromley also lost a brother, Tom, who died from cancer at the age of 19. As a way of dealing with this, Freya decided to swim every tidal pool in Britain and The Tidal Year, tells the story – though the passage we selected describes a dip in a river.

“I booked an Uber to Grantchester Meadows, which involved reassuring the driver that just here is fine please, despite his reservations about why a girl wanted to be dropped off by the river so early.

I walked to a bend in the River Cam and found a wooden ladder. It was simple. It was quiet. It was perfect. There was an orange fire in the sky, dawn had arrived. I undressed quickly. A ruffling in the marshes signalled I’d disturbed a brown hare enjoying its morning by the water. The flamed sky was mirrored on the still pool of water and the meadow blazed with wildflowers. Knapweed, ox-eye daisies, field scabious and meadow buttercups still in bloom. I slipped into the brown water and my heart beat fast, a radiating thud, thud. I heard it in my ears and remembered that I was alive, which often felt like an accidental detail. Blood was being pumped around my body at four miles an hour. I would keep going….

“I inhaled deeply, then placed my head under the water and screamed. Bubbles escaped my mouth like I’d boiled the water with my anger. Jem was right, it helped the rage.”

In the Irish Sea, at Greystones in Co Wicklow, Ruth Fitzmaurice swam her way through the difficult years of caring for her husband Simon, who had motor neurone disease. This is from her memoir I Found My Tribe

“My husband is a wonder to me but he is hard to find. I search for him in our home. He breathes through a pipe in his throat. He feels everything but cannot move a muscle. I lie on his chest counting mechanical breaths. I hold his hand but he doesn’t hold back. His darting eyes are the only windows left. I won’t stop searching. My soul demands it and so does his. Simon has motor neurone disease, but that’s not the dilemma, at least not today. Be brave….

“There was a blood moon last night and the sea is agitated. My soul is agitated. The full moon gets a red glow during a lunar eclipse, says Marian, so watch out. Blood moons belong to moongazers, dreamers and to Marian. For them, the night sky is a realm of intense feeling and romance. I’d never heard of such things, so I lean in closer. We are up to eighty per cent water, Marian says, and that is why the moon and the tides affect us. That is why I jump in the sea, I say. I am trying to find a home, make a home, be a home for my five children. Sometimes I succeed and sometimes I fail.

My friend’s calm cousin cuts through the bullshit, ‘Find your tribe, she says. Finding your people is more important than what kind of house you live in. Decide whether you have found your tribe and go from there. I believe her.

My cove is my tribe and the cove is mine. My babies stand with soggy shoes on the shore, skidding on wet stones and cheer as the Momma plunges to her salvation. Yes, this is my cove and the sea is my salvation.

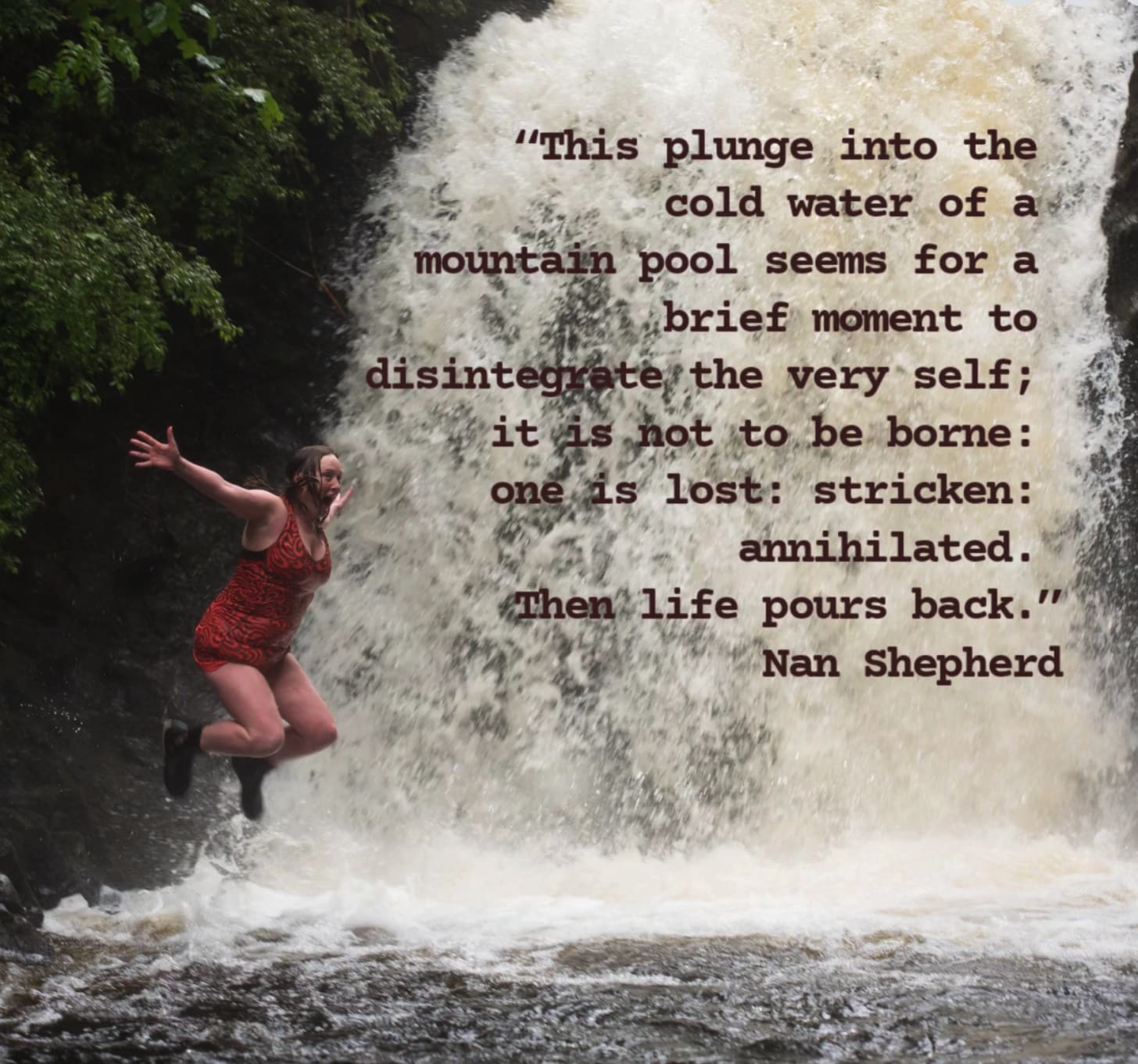

Water can soothe us – it can also jolt us out of destructive patterns. In a passage we chose from the book Vicky created with photographer Anna Deacon, Kenny Neilson tells how his big mate took him to the Campsies in December after he had been hospitalised for near-fatal alcoholism. In the waterfall, Kenny had an epiphany.

“In that waterfall, I was searching for a god. I was praying and I was trying my hardest. I was in the water screaming, ‘Please, God, don’t make me drink today!’ I was broken. I was at a moment of desperation. In that moment in the water when I felt the cold seeping into me, it came to me like that, You’re going to be alright. You’re going to be alright. Then I started laughing. I was howling to myself. I thought to myself, See, if someone was walking down there and saw me, they’d be saying, ‘Who is this big bam?’ They’d be going, ‘God save me!’

Amy Liptrot whose The Outrun was recently turned into a movie also found swimming helped her to recover from alcoholism.

“I want to shock myself awake: after central heating and screens, to feel cold, with skin submerged in wild waters, is attractively physical. I want to blast away the frustrations of being stuck on this island and no longer have the outlet of getting drunk. The chilly immersion is addictive, verging on unpleasant at the time, but I find myself craving it, agreeing to go again, planning my next swim, eyeing up lochs, bays or reservoirs. I want to swim in bomb craters…

“When I pull myself out up the slipway, climbing the ladder onto the pier, or washing up with the waves onto the beach, I feel saved: reborn and very alive….Afterwards, I go about my Saturday – first stop the supermarket – with a crazy smile and bright red salty skin.”

Ciara McCormack in Swimming Wild Ireland told Vicky about how, despite her fear of water, she walked into the sea fully clothed on the Dunany Coast in Leinster one day in winter during the breakdown of her marriage. She emerged feeling like a different person – it was a new beginning for her.

I feel all the things that have happened throughout my life are preparing me for every moment that is yet to come. All the versions of you that you didn’t love, brought you to the versions of you that you love now, so be grateful for the different people you have been.

In Joan Didion’s short memoir about grief, A Year of Magical Thinking, she looks back on swimming with her husband. The line in this excerpt, “no eye is on the sparrow” refers to a childhood hymn about God watching every creature. Joan didn’t believe that – she took comfort instead from her sense of the implacable and majestic indifference of nature to man’s suffering. But after losing her husband, she remembered the way he had told her to be aware of the changing swell of the water. “You had to go with the change.”

“I flew into Indonesia and Malaysia and Singapore with John, in 1979 and 1980. Some of the islands that were there then would now be gone, just shallows. I think about swimming with him into the cave at Portuguese Bend, about the swell of clear water, the way it changed, the swiftness and power it gained as it narrowed through the rocks at the base of the point. The tide had to be just right. We had to be in the water at the very moment the tide was right. We could only have done this a half dozen times at most during the two years we lived there but it is what I remember. Each time we did it I was afraid of missing the swell, hanging back, timing it wrong. John never was. You had to feel the swell change. You had to go with the change. He told me that. No eye is on the sparrow but he did tell me that.”

Marilynne Robinson has a different perspective from Didion. In the second book of her Gilead trilogy, she writes from the point of view of an old pastor called John Ames, writing for the son he knows he won’t see grow up.

“There was a young couple strolling along half a block ahead of me. The sun had come up brilliantly after a heavy rain, and the trees were glistening and very wet. On some impulse, plain exuberance, I suppose, the fellow jumped up and caught hold of a branch, and a storm of luminous water came pouring down on the two of them, and they laughed and took off running, the girl sweeping water off her hair and her dress as if she were a little bit disgusted, but she wasn’t. It was a beautiful thing to see, like something from a myth. I don’t know why I thought of that now, except perhaps because it is easy to believe in such moments that water was made primarily for blessing, and only secondarily for growing vegetables or doing the wash. I wish I had paid more attention to it. My list of regrets may seem unusual, but who can know that they are, really. This is an interesting planet. It deserves all the attention you can give it.”