October events

Vicky and I will be discussing themes from Take Me to the River at:

-

Body positivity: Soul Water Gathering, the Pitt, Newhaven, Saturday, October 18, 4.30 pm

-

Is cold water a cure? Waterstones, West End, Edinburgh on Wednesday, October 22 at 7pm, book tickets here.

We had an event at Wigtown Book Festival last weekend – a wild swim and story circle – and I made a wee reel for social media:

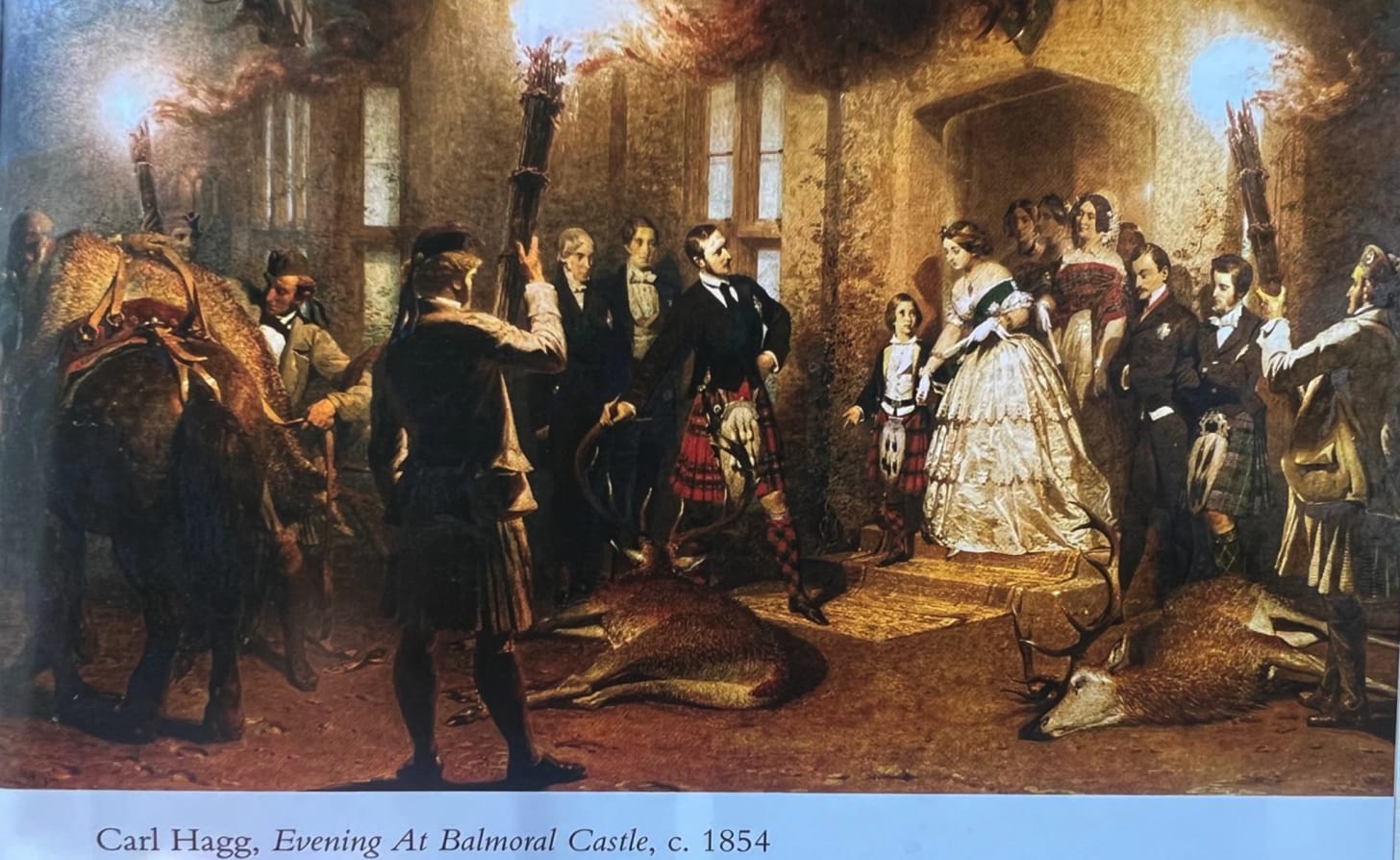

At Wigtown, I enjoyed hearing Fern Riddell discuss her book Victoria’s Secret with journalist Lee Randall. The semi-buried Royal secret that Queen Victoria married her Highland ghillie is the centre piece of the book. It’s something that seems to be dug up at regular intervals before being pushed back underground.

Riddell argued that we ought to acknowledge and celebrate that Victoria found love again in midlife. She was a passionate woman who had a fulfilling second marriage with a handsome, sexy Highlander, a man who was devoted to her and twice risked his life to save her from gun-toting assassins.

Many historians scoff at the mounting evidence for this – the tone is generally (though I paraphrase): “Is it credible that a middle-aged woman who had had nine children could have been interested in sex?”

I asked Riddell if she felt there was an element of misogyny in the reluctance to believe this; and she agreed that there is a prejudice against acknowledging the sexuality of older women.

Randall added that there is also a reluctance to acknowledge that a fat, grumpy older women can be sexual: “When I think of Queen Victoria I don’t see a babe. She was overweight, she looked grouchy – perhaps because they had to sit for so long for photographs – but also she probably was grouchy”.

Riddell countered that in person, Victoria could be lively, funny and charismatic and that the Victorians saw beauty differently – in the whole person, not the Instagrammable image.

She said if Victoria had been a King rather than a Queen, there would have been no issue with her acknowledging her continued sexual appetite after Albert’s death.

Riddell pointed out that when Victoria was widowed, she was just 42 and her fancy may have already turned to Brown. The book includes a picture Victoria gave to Albert which shows Brown at the centre, his imposing presence drawing the eye, though his back is to the artist.

Many people witnessed the pair being intimate after Albert’s death, and Riddell has marshalled them all in her book – the young doctor who saw Victoria hauling up her dress to show Brown a bruise on her upper thigh, the sculptor who sculpted Brown in the nude who also thought they were lovers, the Highland castle they visited where a rap on the royal bedchamber door was apparently heard each night before Brown was admitted.

Victoria had a genealogy constructed to show Brown’s descent from a Jacobite Captain Shaw who was at Bonnie Prince Charlie’s side at the Battle of Culloden – proving to her satisfaction that he was of aristocratic descent. She had a house built for them on the Balmoral estate, where John’s sister was housekeeper and he had the bedroom next to hers. She made her sons shake hands with him and briefly expelled one of them for refusing. Brown even had a scuffle on the dancefloor with one of her sons, when he stopped the music at the Ghillies’ Ball.

When an assassin got close enough to Victoria to wave a gun in her face and say “Take that for the Fenians”, despite her being surrounded by police officers, guardsmen and a couple of sons, it was Brown in his kilt who leapt from the carriage and wrestled the man to the ground. He often carried her in his arms when she was ill or when they were out walking.

Apart from all this, Riddell told us the story of how she found the Brown family’s hidden archive of letters and artefacts, including a letter in which Victoria calls Brown “darling one” and suggestive cards she gave him at New Year. Victoria showered Brown with gifts, including having Albert’s pistols remodelled with a personal inscription.

After Brown died aged 56, from a cold contracted chasing down yet another threat against her life, she had his hand modelled as she had with Albert’s. Victoria was buried with Brown’s mother’s wedding ring on her finger and a lock of John’s hair. The doctor who arranged her body to go in the coffin placed a posy of flowers in her hand to hide the photograph of Brown it contained.

Apart from all this, there is the deathbed confession of the Church of Scotland minister who married them, Norman Macleod, which came to light when the diaries of a cabinet minister were published – why would we discount the deathbed confession of a minister, Riddell wondered?

Riddell argued that she is the only historian who has considered the marriage as it would have appeared in the context of the Highlands. (If true that seems an anglocentric oversight.)

It was easy, certanly, to get married in Scotland then. Marriage in the Church of Scotland is not a sacrament, it is considered part of “the order of creation”. Irregular marriage was a matter of declaration and consent. There is actually a famous case in Scots law where a farmer called his housekeeper into the parlour and declared before witnesses that she was his wife. When he shot himself the next day, she inherited the farm.

So it would have been a simple matter for Macleod to marry them. Victoria was very fond of Macleod, perhaps because of his support in this matter. She certainly mourned him, much more than any Church of England cleric that she knew.

…Many bitter tears has she [Victoria] shed over his [Norman Macleod] loss, and she feels she is poorer again in this weary world without him… For those words of love and truth and wisdom which remained in her heart to strengthen and comfort and cheer her.” “His truly,” Victoria mused, “was the religion of Love. He wished to impress all with the feeling that God was our loving father and not a hard judge.”

I am really glad someone has written this book and made such a strong case (an addendum about a rumour that they may have had a child who was sent to be reared in the New World seems less convincing).

I have always believed the pair were married. When I was a young journalist, I heard a story about a researcher who was working at Balmoral for the Royal family and came across the marriage certificate of John and Victoria. She took it straight to the Queen Mother, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon who was sitting in front of the fire, drinking tea. She looked at it, said “I had no idea it had gone as far as that,” and tossed the paper into the flames.

This unprovable story fits with what Riddell writes in the book – that the eminent historian Harold Nicolson found what he called the marriage lines of the couple secreted in a game book at Balmoral in the 1950s. Fearing they would be destroyed, he simply left them in place. Many of Victoria’s letters and diary entries and other documents were indeed destroyed after her death, seemingly at her request.

Despite all the evidence that theirs was something deeper and warmer than ordinary friendship, there will never be general acceptance that Victoria and John were married without definitive proof. But that is elusive.

Someone once told me that there is something in the Gaelic inscription outside the Loch Maree hotel that says Victoria was married to John Brown at the time of their visit in 1877. I went there one day to look at the stone. The hotel was between owners at the time and closed. A light but persistent rain was dripping down the inscription which was blackened and worn away. It was impossible to take a legible photograph. The Highlands can keep a secret.