With Halloween – or Samhain, as we Celts apparently call it – approaching, Edinburgh city centre is still heaving with tourists. They’re not wrong to come at this time of year: I actually love Edinburgh on winter evenings. The jagged shapes of this high-heapit toon look incredible in the dark, and there’s often some strangely garbed person looming out of the Scotch mist.

But the pavements still seem as congested as they were in July. I sometimes borrow the language of the road and mutter “beep beep” as I try to squeeze past the dawdling hordes. The other day a young woman with a blonde ponytail – I’m guessing a newly arrived student princess – cannoned straight into me as she jogged assertively down North Bridge.

It’s not just the pavements. The roads are gridlocked too, and when an Uber driver attempts an illegal manoeuvre, the whole city echoes with judgmental horns. Apparently, Edinburgh is now the most congested city in the UK, and drivers spend 40% of their time in jams.

Recently, after a day working in the National Library, I went to an evening meeting at the City Chambers to hear a presentation about plans to reopen the city’s suburban railway line. And what a great idea it is – a huge lever for the city to pull.

Edinburgh has a ghost line that circles the town. It currently carries about four freight trains a night, and that’s it.

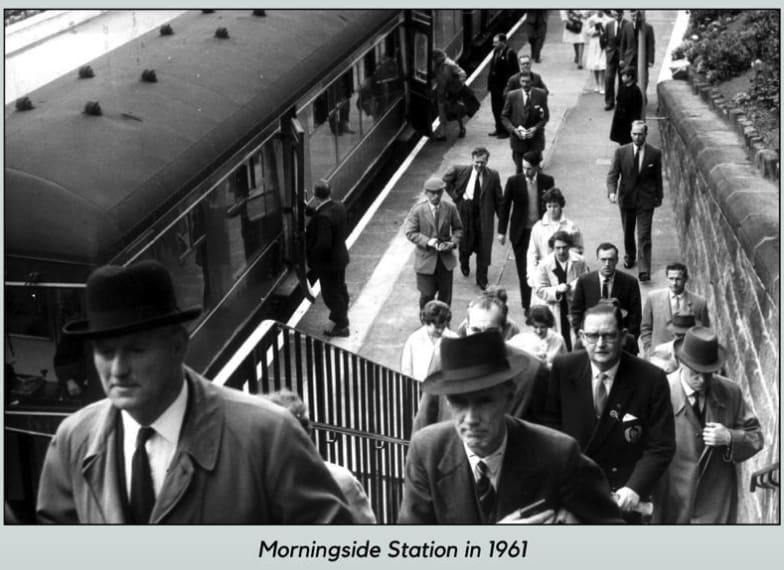

It was closed to passengers in the 1960s – the era when fossil fuel companies lobbied, persuaded and bribed city councillors everywhere to mothball their suburban trains and rip out their trams.

In the long term that has been a disaster for Edinburgh as for other cities – like Glasgow. The exceptional tram system Glasgow once had, closed in 1962. It was one of the largest in Europe, with a thousand trams covering a hundred route miles: emission-free, affordable public transport reaching every part of the city. Many tram drivers were women – they lost their jobs as they were barred from driving the replacement buses, which were said to require greater physical strength. Glasgow, though, did better at protecting its suburban rail lines.

Meanwhile, back in Edinburgh, the car era has meant that some of the most awkward journeys in the city – say, from the centre to Portobello or Morningside – are probably slower than when we had horse-drawn coaches.

And the noisy, fume-laden vehicles that now clog our streets don’t leave enough room for pedestrians. Oxford – another tourist-heavy city – has removed private cars from its centre, giving space back to pedestrians and cyclists. Edinburgh needs that kind of breathing room.

The circular line is still there waiting, and it’s still in use as a railway. People have been lobbying on and off for decades to reopen it. The sticking point has always been capacity: the line between Haymarket and Waverley is almost completely full, and any spare slots are needed for the London service.

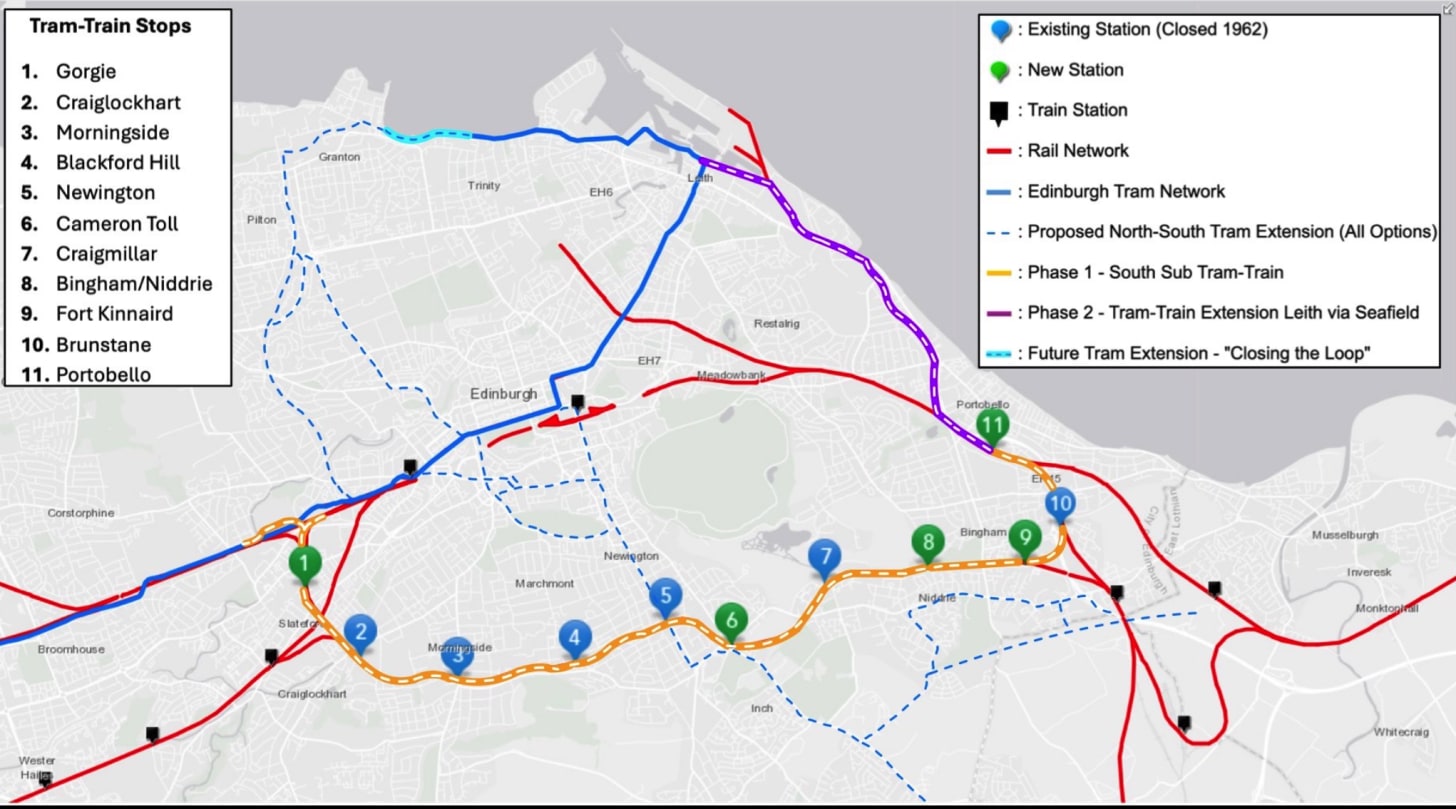

The game-changing idea is to use tram-trains. As engineer Corey Boyle explained to us at the meeting, “it walks like a tram and it talks like a tram, but it’s actually a train.”

These vehicles, which are being used in Germany. have dual wheels – they can run on standard railway tracks and then transfer seamlessly onto street-level tram lines, avoiding the bottleneck at Waverley and Haymarket altogether.

Boyle, part of a team of Heriot-Watt University engineers, carried out a detailed feasibility study that’s now being championed by a new group called Tram Trains for Edinburgh (TTfE). Their plan would see a 12.3 km route from Murrayfield to Portobello, with stops at Craiglockhart, Morningside, Newington, Cameron Toll, Craigmillar, Fort Kinnaird and Brunstane – all for a fraction of the per-mile cost of Edinburgh’s new tram lines.

The beauty of it is that it would use existing infrastructure – tracks that already run through some of the city’s most under-served areas – and finally give the south side the kind of public transport it’s been promised for decades. There’s even potential for a Cameron Toll interchange, allowing future connections south to Dalkeith and Midlothian.

Some argue that money should go into more buses instead, but it wouldn’t cost much less. And buses add to the gridlock as they queue at stops. Travel times are slowing every year – by as much as 10% on some routes. The new electric buses are good for emissions, but they struggle with Edinburgh’s hills.

I was on board an electric bus this summer as it failed to summit Dundas Street. The driver kept trying to restart, but the bus rolled backwards a foot or so each time. Eventually she opened the doors in the middle of the road and a number of passengers – myself included – piled out to lighten the load, and she was finally able to get over the top. Not exactly a vote of confidence in the electric future.

It’s not often a city like Edinburgh gets the chance to do something visionary that’s also great value for money. This is one of those rare cases where practicality and imagination align – a chance to reuse and recycle an existing asset that was mothballed by the fossil fools of the late 20th century.

If it works, it could take thousands of cars off the roads, make Morningside and Portobello commutable without stress, and let us enjoy our dark, misty evenings without the soundtrack of horns and idling engines.