I wrote last month about Scotland’s million-deer problem and how that is affecting the Highlands. The animals crash onto the road causing accidents, injury and sometimes death. Hillsides are left bare with slim pickings for other creatures. Starvation is their most effective predator.

The deer-stripped landscape is beautiful – but it isn’t natural. It’s been created over centuries by a small number of landowners – and they have left Scotland with biodiversity far poorer than most comparable countries.

Watch Lesley Riddoch’s short film Scotland’s Missing Forests – about what should be here – and what could be again with better stewardship.

But how did it come to be like this?

I wrote recently about the land grab that was going on in the background of the Reformation and the overthrow of Mary Queen of Scots by a band of rapacious warlords. (Their descendants, thanks to the system of primogeniture, still own a big chunk of Scotland today.)

In 1603, Mary’s son Jamie Saxt took over the throne of England and headed to London – never to return except for one short visit.

A bunch of nobles travelled south with the King. They needed hard cash in their pockets more than ever – so the much richer lords and ladies they met there would not look down on them.

First, they cut down swathes of the Caledonian forest and sold the timber for cash.

About this time, Scotland’s map maker, Timothy Pont (1565-1615) explored the country – we have his account, for example, of the verdant forest around Loch Maree. Now largely bare except for a bit of commercial timber – which does not support the insects and birds of the area, back then it was teeming with Scots pine, holly, oak, ash, birth, elm. Pont spotted “fair and beautiful fyrrs of 60, 70, 80 foot of good and serviceable timber.” Pont’s work helped the lairds identify the most profitable timber.

After cutting much of it, the “nobles” were next able to exploit tariff-free access for Scottish goods to English markets that Jamie Saxt put in place.

Cattle in the black

They set about expanding the trade in black cattle, which they pushed to habitat destruction in pursuit of profit.

A.R.B Haldane’s classic of Scottish history “The Drove Roads of Scotland” tells the story of this trade and the men who plied it. He wrote:

”By the middle of the seventeenth century, the cattle trade to England had grown to such proportions that Scotland was described as little more than a grazing field for England.”

Under the new economic rules that came after the Union of the Crowns, it was very profitable to move Scottish cattle south. The Scottish lairds could undercut the price of English animals at York, but still make big profits thanks to the lower cost of production and the lower wages they paid to the workers.

It is fascinating to read about the hardy Highlanders who followed their beasts south, sleeping outside, eating little more than oatmeal, occasionally bleeding the cattle to make black pudding to supplement their meagre rations. Their loyalty to their chieftain was a pre-feudal habit. They made few demands and took great personal risks to move the valuable stock across dangerous country.

Haldane quotes Walter Scott in The Two Drovers: ‘The Highlanders in particular are masters of this difficult trade of driving, which seems to suit them as well as the trade of war. It affords exercise for all their habits of patient endurance and active exertion. They are required to know perfectly the drove roads which lie over the wildest tracts of the country, and to avoid as much as possible the highways which distress the feet of the bullocks, and the turnpikes which annoy the spirit of the drover ; whereas on the broad green or grey track, which leads across the pathless moor, the herd not only move at ease and without taxation, but, if they mind their business, may pick up a mouthful of food by the way.’

(This summer, ecologist and farmer Richard Lockett recreated a drove – through a green but largely treeless landscape.)

The crofters had managed animals to protect the woods

For millennia of course, cattle had been part of the ecology of the Highlands. But the animals were managed, herded and and the woodland was protected from overgrazing Mairi Stewart wrote in “People and Woods in Scotland”:

“To the Highlander, woods were particularly important as a critical source of winter shelter and spring grazing, where cattle could get their first bite of new grass before they were sent to the hill sheilings. As long as the animals did not do too much damage to seedlings and saplings, which would later replace the older trees needed for all the essentials of life, the woods would continue to flourish. But a tree’s ability to put out new shoots after cutting would be negated if hungry mouths then sheared them back. And, if this happened, year after year, eventually there would be no young to replace old. Woods would become pasture with scattered trees, old and decaying, then lost forever.

“Country folk had their own ways of managing stock and woods to produce grass and timber. These ways, largely unknown to us, might have sufficed to keep the woods in good heart had it not been for forces at work beyond their ken which changed their way of life and their woods.”

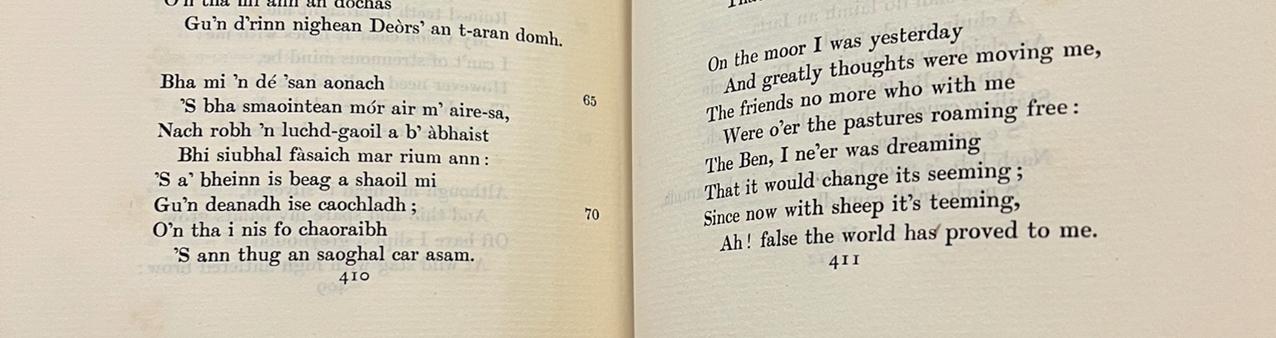

Sheep were later brought in as a profitable cash crop. The woods started to disappear under this pressure of grazing. The great Gaelic nature poet Duncan Ban MacIntyre (1724 -1812) lamented the destruction of the woodlands he loved by over-grazing.

The shooting estates then started to offer the most profit

As the habitat degraded, deer and grouse started to become more profitable. At that point the lairds either opened shooting estates themselves or they rented their land to the rising industrial class which used them to impress and to gain access to the aristocratic elite.

An invitation to a shooting party was an entree to the governing class. (Trollope’s “Palliser” series. which I quoted from in part one is beatifully read by Timothy West on Audible, and most of them feature gatherings of this kind.)

The transition to sheep and shooting involved clearing many of the people and families who lived here. By the nineteenth century, the Highlands had been violently reorganised for profit, leaving glens emptied and communities broken.

John Prebble wrote in the intro to his seismic “The Highland Clearances”:

It has been said that the Clearances are now far enough away from us to be decently forgotten. But the hills are still empty. In all of Britain only among them can one find real solitude, and if their history is known there is no satisfaction to be got from the experience.

I’m going to come back to that story in a separate piece. What matters here is what the landscape itself still shows: how in pursuit of profit and influence, the landowners tried to cut out the human heart of the place.

The destruction of the human ecology of the Highlands led to its current fate – large estates to be managed and improved by external forces rather than a home.

Healing the Highlands starts with its people

Now so much of the Highland is owned in huge parcels to be bought and sold – or inherited with few restrictions, it is attractive to the megarich, and to companies who want to invest in carbon credits or commercial timber. The market is pushing the wrong way and the Scottish government’s timid land reforms have not been enough to tip the balance.

Even charities and the green lairds today who say they want to “rewild” the Highlands talk more about introducing lynx and wolves than about affordable housing. (1)

We should start seeing communities as the solution – and meaningfully broaden ownership so the fate of the Highlands is no longer gripped tightly in the hands of a few companies and mega-rich individuals.

We could look to Finland where land ownership is broad across society and stewardship decisions are shared not imposed.

It was Highlanders long ago who took care of the woods and managed the animals in sophisticated ways that we barely understand and should stop looking down on. They could do that again. The healing of the place has to start with supporting the recovery of its human heart.

(1) A weekly programme on BBC Radio 4 called “The Patch” went to Gairloch last month and highlighted the impact on the school rolls from the lack of affordable housing, which I also wrote about here